Hormones, steroids and more

Protein drinks and dietary supplements are in the focus of Landeslabor Berlin-Brandenburg

Landeslabor Berlin-Brandenburg, the region’s state laboratory, is engaged in regular testing of protein drinks and dietary supplements as part of the German government’s official food control. Inspectors are on the lookout not only for banned substances but also for inaccurate quantity declarations and unlawful labelling. As part of a recent state-level programme, an increased number of samples from fitness studios in Brandenburg are being taken and analysed for undeclared substances.

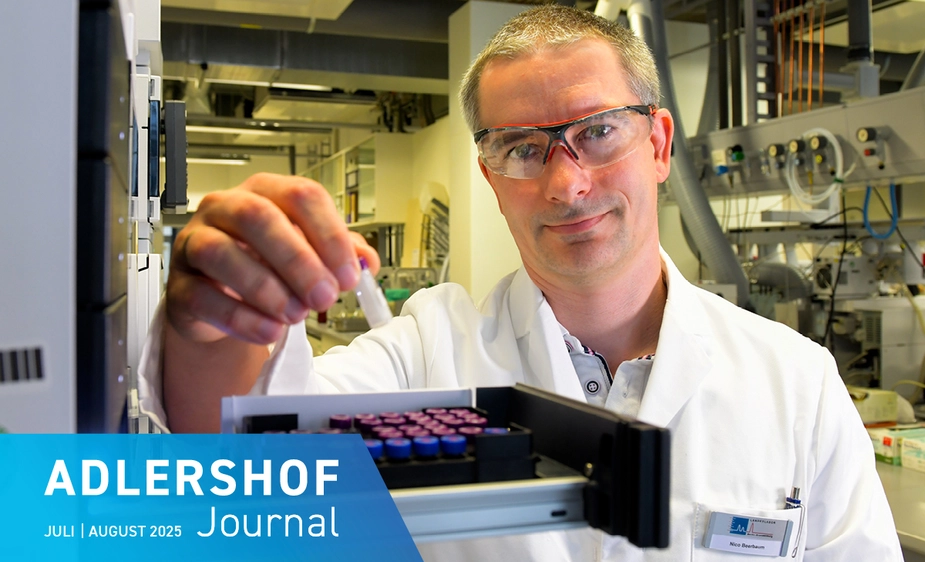

Protein drinks and dietary supplements (DS) play an important supporting role in sports. They provide increased protein intake or cover a higher demand for vitamins, minerals, and other micronutrients. However, the market also includes manufacturers promoting miracle products for weight loss or rapid muscle growth, often with false ingredient lists. Some contain prohibited plants and substances. Food inspectors from Brandenburg’s various districts are currently conducting unannounced checks in gyms. In total, 17 samples each of protein drinks and dietary supplements then undergo comprehensive analysis. “We compare the results against databases listing around 9,200 substances. They range from anabolic steroids, narcotics and growth hormones to steroids and weight-loss agents,” says Nico Beerbaum, head of testing for undeclared substances.

These databases are continuously expanded over time. Constant updates and regular exchanges with other control laboratories ensure high-quality analytical results.

According to Madlen Barth, head of dietary supplement testing, checks at fitness studios are still in their early stages. The same applies to protein drinks, says Eric Rußbült, who oversees this sector. The results from the first three samples were fine, but much work remains to be done. While 17 samples per category might seem few to laypersons, it requires considerable effort. Unlike targeted testing for a specific substance, the approach here is reversed. The results are compared against the full database of 9,200 substances. Sometimes it takes days to confirm a result.

Any irregularities are reported back to the district supervisory authorities. Inspectors must be confident in the accuracy of their findings.

The state laboratory’s other programmes conduct checks on DS that are distributed online. Here, there are more frequent hits, especially among products promoting increased potency and weight loss. Many manufacturers operate close to the “pharmaceutical borderline,” as supplements—unlike medicine—do not require approval. Protein drink testing primarily focuses on protein content, where cheating can occur. Adding to this are labels claiming they contain “no added sugar”. “We also check whether sweeteners are declared or possibly forbidden, or if maximum levels are exceeded,” says Rußbült. Amino acid quantities are sometimes incorrect, which affects protein quality.

When samples arrive at the laboratory that were seized by customs, police, or the state criminal investigation office, the detection rate is significantly higher. Monitoring of protein drinks and dietary supplements is gaining importance as sales of these products increase, leading to more frequent testing. Because of worldwide distribution, inspectors agree that samples from online commerce show more irregularities. In traditional retail trade, individual cases might reveal substantive issues. On-site controls contribute to prevention.

Kathrin Reisinger for Adlershof Journal